The Big Picture

- Disney animator Andreas Deja takes us into the animation studio for some of Disney’s classic films like The Lion King, Aladdin, and more.

- Animators have a significant influence on the character, working with rough sketches, the voice actors behind, and their own creative imaginations to establish the character’s movements, expressions, and personality.

- Deja also shares the inspiration behind his upcoming short film, Mushka.

For one hundred years, Disney has been the industry standard when it comes to animated family films. Classics like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, and Beauty and the Beast are still held in high esteem and introduced to the next generation, inspiring new and innovative stories. Yet audiences often overlook the folks behind the animation itself, who turn drawings or 3D polygons into living, breathing characters.

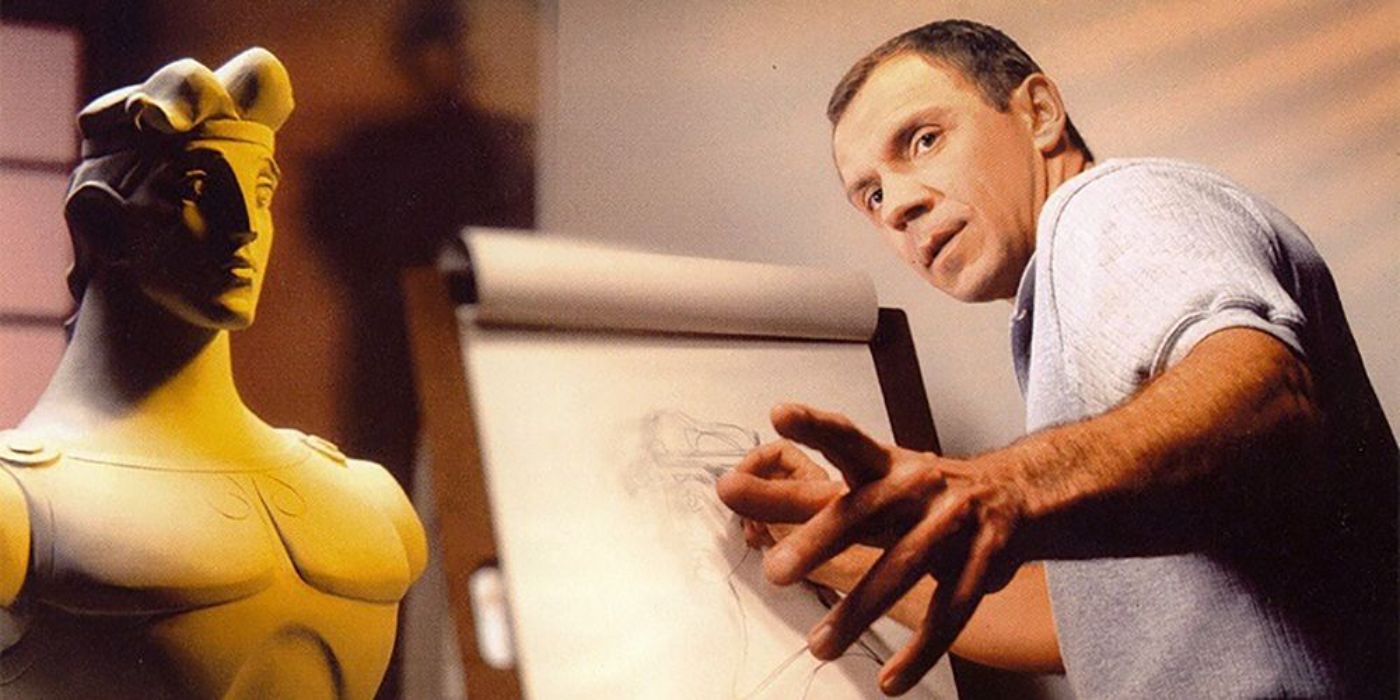

One of these animators is Andreas Deja, who was inspired by Disney films such as The Jungle Book and The Aristocats. He joined Disney in the 1980s as one of many new artists meant to learn from and succeed the Nine Old Men. Over thirty years, Deja designed and worked on many beloved Disney characters, including three of their biggest villains: Gaston, Jafar, and Scar.

As Deja prepares for the release of his short film, Mushka, he agreed to sit down and give some insight into the creative process behind animated characters and how those experiences influenced his work. For the sake of convenience and clarity, the conversation is presented in an abridged form.

The Challenge of Creating Unforgettable Disney Villains

TYLER B. SEARLE: You have worked on some of Disney’s most recognized characters. Particularly the trio of villains you made during the Renaissance. From your experience working on those characters, what do you think goes into making a good animated villain?

ANDREAS DEJA: I think the challenge is to go beyond the idea that this character is “bad.” The character also has to be interesting. Whether the villain has a sense of humor or has a way of phrasing their dialogue… You go through the whole list of characterization and see what might work for your character to go beyond just being evil, because that’s just not enough and would be rather boring. And then, of course, I always got a lot out of the voice recording. The voice recording in animation is always done first, the actors come in, and then we get that material to listen to. And it really is as simple as the animator just closing their eyes, and then you just listen to these phrases and things come to mind. Pictures appear, and you get a sense of what this character might look like and what the character might also move like.

That leads to another question: how much influence do you have on the character? Since the voice recording is done first, do you not necessarily have a lot of input?

DEJA: It’s actually quite the contrary. It’s really me who is the actor of this character and I will show and demonstrate how the character moves, how the character thinks and schemes. So the acting is really all mine. Of course, it’s based on the voice, but many, many scenes don’t have dialogue. The old phrase that animators are actors with a pencil, is absolutely true. You can compare it to the world of live-action even more in the way we work. I get an assignment and a few scenes to animate, then I look at the storyboard, and I talk to the directors about the motivation of the character here and what he’s feeling. So it’s very much what a live actor would talk about to a director. Then it’s up to me to go to my office and demonstrate what this would look like with pencil and paper.

Do you have any favorite examples of one of your villains where you did just that: speaking with the directors to get the perfect personality for them?

DEJA: Probably all of them, but the one that sticks out because the quality of the voice was so outstanding was Scar in The Lion King. I worked with Jeremy Irons, and he made it easy for me. He gave Scar intelligence and a sense of humor. You combine that with evil and that makes an extra dangerous villain. Scar also really enjoyed being evil. He liked toying with his victims. In the first scene, he slaps his paw down, picks up the little mouse, and is toying with this little animal.

It was tricky from the point of view of portraying this lion with weight and making him feel heavy and real, but the actual understanding of the character and coming up with acting patterns was fairly easy and a real joy. And setting the design, which is also the job of the supervising animator. You’re not the first one to design the character: I can look at story sketches where the character is portrayed in a loose form and some visual development drawings, but it’s really up to me to do the final version and decide that this is what works for me. In the case of Scar, I not only listened to Jeremy Irons, but I also watched some of his movies and got some photos. I thought, “What if I base his appearance a little bit on Jeremy Irons?” That’s not always the case. The previous one was Jafar for Aladdin, voiced by Johnathan Freeman, and he doesn’t look anything like Jafar whatsoever.

Creating Disney Heroes Begins on the Inside

You’re not just known for your villains. You’ve also done King Triton, Lilo, and adult Hercules. What do you think is required to make a really good Disney protagonist?

DEJA: It’ll be similar to what I said earlier about the villains. They cannot just be nice and gentle and sweet — they have to be interesting with a full-fledged personality. Let’s take Lilo. She is a lonely little girl in this broken family, as she would call it. Having done villains, you shift gears when you get an assignment like that. It’s about other things: the inner feelings of a lonely little girl who wants a friend. She was a character I animated from the inside out. I felt her loneliness and frustration, wanting to be good, but failing sometimes.

With Hercules, he was shy, especially around girls, and he didn’t have any confidence yet. He’s trying to be good and be a hero. You think of those characteristics and poses that come to mind. You bend the character forward a little bit when he’s unsure and doubts himself. I had one really challenging acting scene. When Meg is about to die, and he’s holding her upper body, she cracks a joke. We cut to his close-up, and he tries to laugh, but it’s really not a funny situation at all. So you have both: he’s trying to laugh at her joke, but there are all these different things going on in his head. It was a challenge, but a really interesting challenge.

During the early Revival Era, you worked on Mama Odie from Princess and the Frog and Tigger from Winnie the Pooh, and further back you worked on Roger Rabbit from Who Framed Roger Rabbit. What goes into bringing to life a comic relief character, and how do you animate them without losing people in how zany they can be?

DEJA: Interesting question. Here again, even though you might have an eccentric design which has more caricature than the prince or princess, you still want them to have weight. Without weight, the character kind of floats and you lose the audience. When a character takes a step, the knee has to bend to show that the weight is coming onto that leg. Mama Odie has that: she’s this short chubby character with eccentric expressions, but when she jumps, her knees bend, and you get a sense that this old woman weighs a certain amount.

When you have a character like Roger Rabbit, he is so cartoony and so surreal that you can do almost anything with him because there is no reference point. There is no Roger Rabbit or anything like him in real life. So you can have the eyes pop out and do these Tex Avery takes. He was the most surreal character I’ve ever done.

The Magic Behind ‘Mushka’

Where did the inspiration for Mushka come from, and how did the original inspiration change during the production?

DEJA: It changed early on. I kept asking myself. “What would be fun to animate?” I knew I wanted to have an animal involved, and I love tigers. I’ve done big cats like lions way back on The Lion King, and a tiger moves similarly to a lion. I could apply that knowledge to Mushka. Why don’t I pair that with an innocent little girl? Then I fleshed it out more in my mind: what if the girl raised a tiger cub? The tiger grows, and the characters bond, but the girl finds out that some bad people want to kill her tiger and sell the dead body. The only way she can save him is to take him back to the place where she found him.

That’s all I had, and that’s not a story, it’s an idea. Then you reach out to friends who have experience with storytelling. I have a very good friend who has written novels, poetry, songs, and architecture — all sorts of artistic outlets. I said, “You can probably help me out with this.” My friend was exploring an Indian village because that’s the first thing that came to mind: tiger, India. He called me saying, “Something is too familiar and not fresh enough. There’s already Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book with Mowgli and Shere Khan.” Then I thought, “Wait a minute. We don’t only have tigers in India. The biggest tigers in the world are in Siberia. Let’s go there!”

What are you hoping audiences will take away from the experience?

DEJA: I certainly hope that they enjoy watching the film and that someone here or there might shed a tear. It’s also a reminder that drawings have the power to become real characters and tell a meaningful story. I don’t hide the fact that these are drawings. They have dark outlines around them and I kept the animation loose and sketchy. But you still believe that this is a real girl, you still believe this is a real tiger. That’s the magic trick about the whole thing.

Andreas Deja’s Disney work can be streamed on Disney+.

Watch on Disney+