The Big Picture

- Biopics are movies, not documentaries. They exist to entertain, not solely to teach or present historical accuracy. Even with accuracy, a biopic has to tell a story that engages the viewer.

- The limitations of time in a biopic mean that filmmakers have to be selective in what they present. They can choose to present facts and timelines accurately but risk an exceptionally long runtime, or condense events, merge timelines, and take artistic license to create a narrative that captures the spirit of the facts.

- The film Rocketman successfully bridges historical accuracy and storytelling by exploring the inner, emotional life of Elton John. It presents a fairly accurate recreation of his life but does not strictly adhere to chronological events. It emphasizes the feelings behind the events, making it more compelling for the audience.

Biopics are an odd genre, one that runs the gamut from serious Oscar contenders like Lincoln to wacky half-truth efforts, like Weird: The Al Yankovic Story. From the historical accuracy found in She Said to a narrative effort in the vein of Spencer, which took creative liberties to flesh out Princess Diana‘s (Kristen Stewart) story. But what should a biopic focus on more? It’s a topic that has long been debated, ever since Georges Méliès released Jeanne d’Arc/Joan of Arc in 1900, and the release of Ridley Scott‘s Napoleon has reopened the topic for debate, especially given how Ridley Scott has been openly dismissive of historical accuracy in regards to the film. There are arguments – well-thought-out arguments, at that – on either side of the debate, but that doesn’t answer the question. What should a biopic focus on more? As much as accuracy should be a goal, the truth is that a biopic has to tell a story, even if that narrative trumps history. Here’s why.

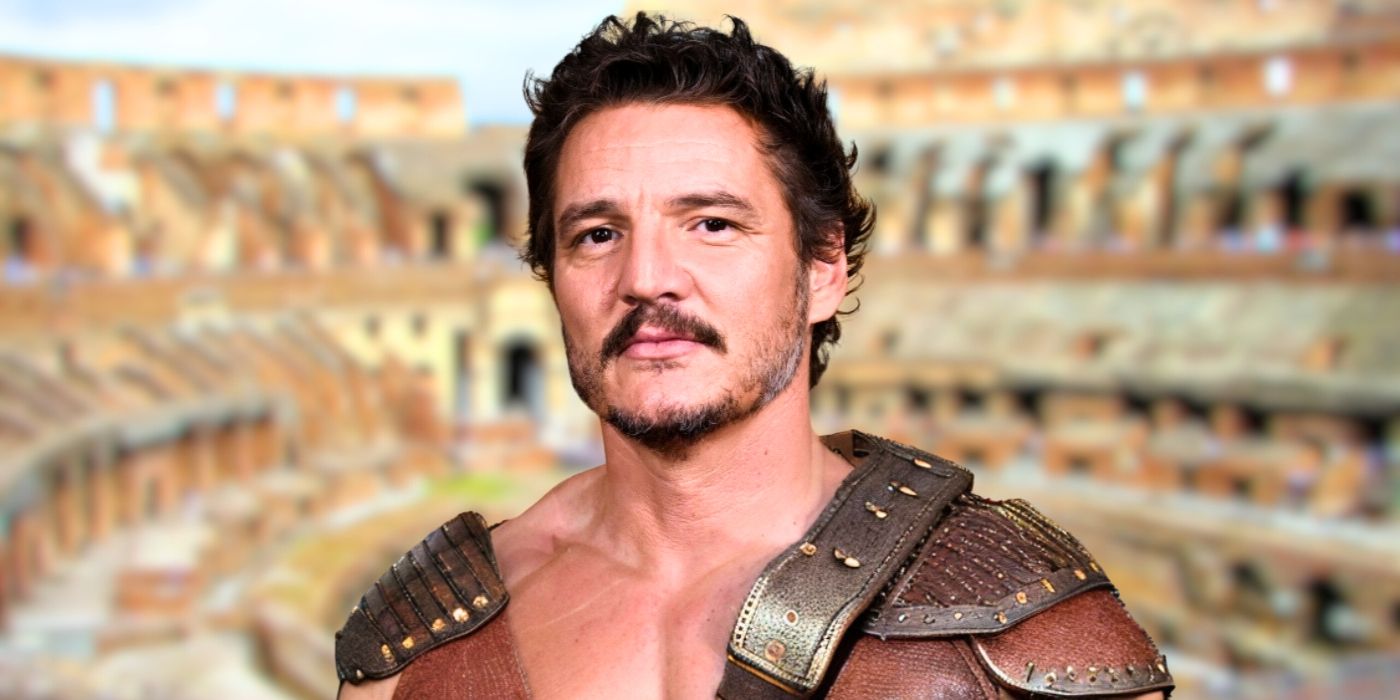

Napoleon

- Release Date

- November 22, 2023

- Director

- Ridley Scott

- Cast

- Joaquin Phoenix, Vanessa Kirby, Ben Miles, Ludivine Sagnier

- Rating

- R

- Runtime

- 157

- Main Genre

- Biopic

Biopics Are Not Documentaries

A biopic is a movie, first and foremost. Simplistic statement, or something deeper? A little of each. The strikingly obvious point actually opens up a wider debate: what exactly is a movie? Generally speaking, a movie exists to entertain the viewer, and how that is translated largely depends on the intent of the filmmaker, be it comedy, horror, drama, or some combination thereof. As far as biopics go, then, if we believe a biopic to be a movie, then it exists to entertain, not teach. It’s rare that one would ever hear a director say that the intention of the film is to be 100% historically accurate, based solely on facts. Steven Spielberg didn’t break his childhood down to minute details for The Fabelmans, he simply wanted to share his story. Sofia Coppola read Elvis and Me, the 1985 memoir by Priscilla Presley, and it inspired Sofia to tell Presley’s story in Priscilla. Even James Cameron, so meticulous about the tiniest of details in Titanic, had to present those facts within the story of Rose (Kate Winslet) and Jack (Leonardo DiCaprio), the ill-fated, fictional lovers on board the ship. Not that movies don’t exist that are entirely true to facts. They even have their own genre: documentary.

That’s not to say that a film can’t portray history accurately, be used to point out society’s ills, or even educate. Biopic films like Schindler’s List and Selma are powerful, powerful depictions of the Holocaust and the 1965 “Bloody Sunday” march in Selma, Alabama, in order, but use the dramatic element of film to bring the truths to relatable life. In the previously cited article in The Vulture, Napoleon‘s Joaquin Phoenix sums it up very nicely: “If you want to really understand Napoleon, then you should probably do your own studying and reading.”

What Makes a Good Biopic Movie?

Biopics only have so much time to tell a person’s story on screen. Walk the Line condenses 44 years of Johnny Cash‘s life into 136 minutes. Gandhi uses just over three hours to tell the tale of Mahatma Gandhi between 1893 and 1948, 55 years in total. Even if you don’t buy into the “a biopic is entertainment” argument above, you can’t argue that the limits of time have an unavoidable impact on how much can be told in a biopic. Every movie has an ending. Every TV series has a finale (with the exception, apparently, of The Simpsons). A filmmaker can only fit a limited amount of a person’s biography into a feature film. And the people whose lives get turned into biopics, by and large, are people who’ve led, and/or continue to lead eventful lives. Thus, by its very nature, a biopic has to be selective in what is presented.

The biopic filmmaker, then, has some choices to make. Tell the story of the subject with nothing but historically accurate facts and timelines, while trying to make a film that is still engaging, or play around with facts, events, and timelines to fit in as much about the person as they can. The former would produce a film with an exceptionally long runtime, testing the endurance of the hardiest of moviegoers, while the latter tells the narrative in a shorter runtime, keeping the viewer’s interest while staying true to the spirit of the facts. This is why so many biopics tend to merge events, condense timelines, avoid specific details, or take artistic license to dramatize a summation of events.

In an interview with The Times, Ridley Scott references one scene in Napoleon, where Napoleon’s cannons fire at the Pyramids in Egypt, which speaks to that very point. Says Scott, “I don’t know if he [Napoloeon} did that, but it was a fast way of saying he took Egypt.” Historically accurate, just summed up in a single moment. Braveheart eschews facts from the get-go, depicting the Scots wearing kilts in the 13th century, when they weren’t worn until the late-16th century, and dramatizes the Battle of Stirling Bridge in a scene completely absent of any bridges, let alone the one it’s named for. But visually, you know it takes place in Scotland, and the battle is far more exciting than it arguably was in life, where the Scots waited for English troops to cross the bridge in smaller groups before attacking. By doing so, Mel Gibson eliminated the need for time-wasting exposition and a long, drawn-out action piece light on action. And that’s just two examples of the practice. Collider is one of many websites to feature articles about historical accuracies, or the absence of them, on film.

‘Rocketman’ Nails Both Its Storytelling and Historical Accuracy

Now all that said, a biopic can be both historically accurate and narrative, and one of the most recent films that managed to successfully bridge the two is 2019’s Elton John biopic Rocketman. Of the film, director Dexter Fletcher tells Esquire, “There could be a factual, chronological documentary that would tell you absolutely everything about what Elton did, where he was, and when he did it, but the film just absolutely explores his inner, emotional life.” The movie is a fairly accurate recreation of John’s life, with his song catalog appearing throughout the film… but not in the chronological order he made them. He performed Crocodile Rock at the Troubadour but certainly didn’t levitate while doing so. Fletcher kept to the facts but made an artistic decision to depict not the events themselves, but the feelings behind them.

In doing so, Fletcher gives what is arguably the most compelling example of why historical accuracy should take a backseat to the story, from the same interview: “Memories are not ‘I went down to the shop and bought a pint of milk.’ You know, that is a particularly dry story. If you say, ‘I went down to the shop and I bought a milk bottle, but I was actually freezing and starving because I had no money, and it was the most important pint of milk I ever drank at that particular time in my life,’ it’s now about the emotional content of that. That makes it interesting.” Facts are definitive and straightforward, but the story behind those facts is interesting, and there is no better medium than a movie to paint a picture of those stories. So if you bemoan the lack of historical accuracy in biopics, it would serve you well to heed Phoenix’s suggestion and hit the library, not the multiplex. But bring your own popcorn.

Napoleon is now playing in theaters.

Buy Tickets Here