The Big Picture

- Critics and mainstream audiences in 1983 did not appreciate Scarface due to its bloated runtime, excessive violence, and heavy-handed thematic and stylistic components.

- Scarface was initially panned as a trashy B-movie with little critical reverence, but it found a new lease on life within the hip-hop community in the following decade.

- The references to Scarface in hip-hop songs, such as those by Jay-Z and Nas, helped solidify its legacy and make it a cultural fixture in the genre.

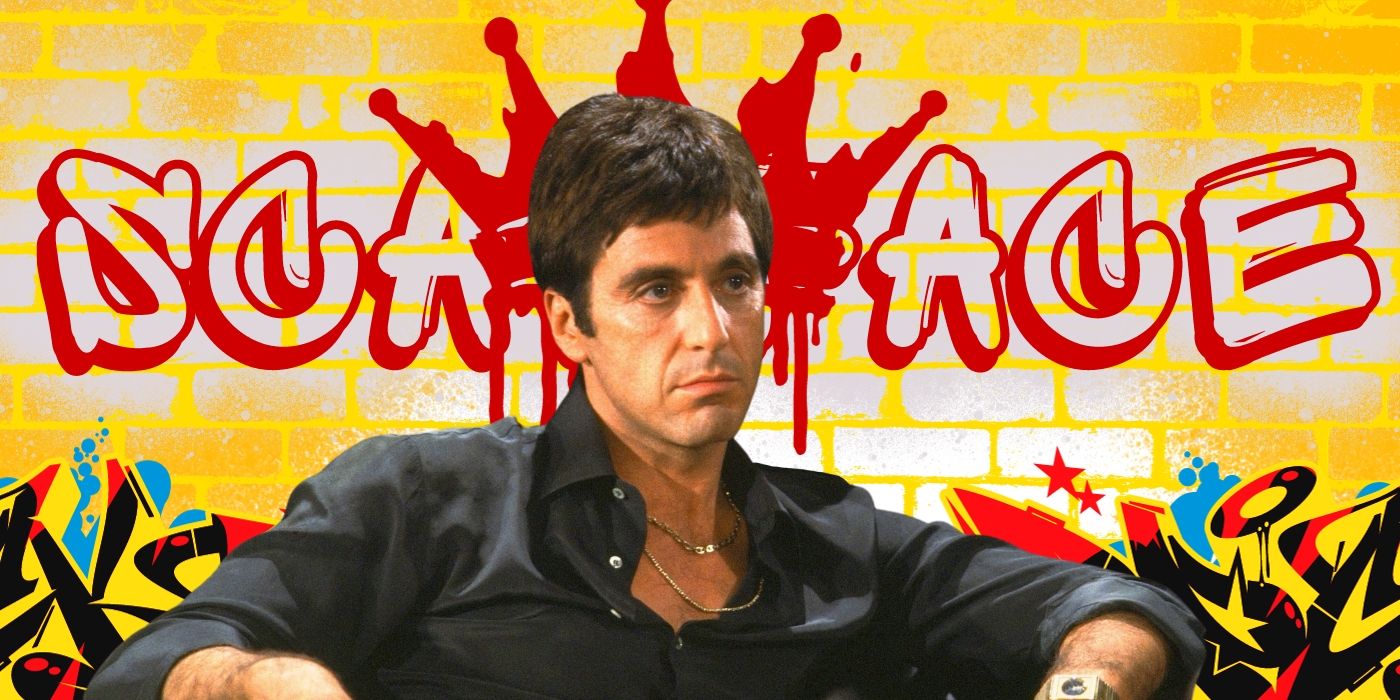

In retrospect, it is safe to conclude that critics and mainstream audiences in 1983 simply did not get Scarface. The bloated runtime, excessive violence and profanity, and the heavy-handed thematic and stylistic components of the film had critics baffled, and even disgusted. Scarface, a remake of the 1932 classic of the same name by Howard Hawks, was destined to remain a footnote of the careers of director, Brian De Palma, screenwriter Oliver Stone, and star Al Pacino. About a decade following its disregarded arrival, Scarface struck a kinship with the hip-hop community. As soon as allusions to the once-disgraced film started popping up in songs by Jay-Z and Nas, Scarface‘s reappraised legacy has never looked back.

‘Scarface’ is Met With Negative Reviews Upon Release

Released on December 9, 1983, Scarface, centering around Cuban immigrant Tony Montana’s (Pacino) rise and fall as a greedy and hot-tempered drug kingpin, had a long uphill battle to amass the critical reverence of the classic gangster pictures like The Godfather. Unfortunately, the film was panned for its trashy, B-movie qualities — something that should be expected considering it was a Brian De Palma film. Pauline Kael, an advocate of De Palma’s distinct voice, criticized the sluggish pace and formlessness of the characterization of Tony Montana, with the original headline in her review for The New Yorker reading “A De Palma Movie For People Who Don’t Like De Palma Movies.” While Roger Ebert gave it a proverbial thumbs up, Gene Siskel was not a fan, finding it “empty,” and the character of Tony “tremendously boring.” Between its common critiques, on top of its questionable depiction of Cubans almost entirely portrayed by white actors, Scarface appeared to be nothing more than a curious experiment that suffered the same cataclysmic downfall as Tony Montana.

Within the next decade following Scarface‘s unfavorable release, De Palma would experience the highs of directing The Untouchables and lows of directing the notorious flop, The Bonfire of the Vanities, while both Pacino and Stone would go on to win Academy Awards, with two wins for Best Director for the latter. While the rest of pop culture moved on from Scarface, the booming art form of hip-hop music began embracing the film as a text of worship. As Steven Bauer, portrayer of Tony’s friend and right-hand man, Manny, stated in a New York Post interview, “Scarface was dead and buried until hip-hop rediscovered it.” Ostensibly overnight, quotes and references from the 1983 film were woven into the fabric of hip-hop culture — a phenomenon that had risen from the underground to the mainstream.

References to ‘Scarface’ Become Ubiquitous in the ’90s Hip-Hop Scene

De Palma’s film was evidently formative for two icons of the 1990s hip-hop scene, Jay-Z and Nas. The immensely profitable and towering career of Jay-Z began with a reenactment of Omar Suarez (F. Murray Abraham) offering Tony a lucrative drug deal in the opening track, “Can’t Knock The Hustle” from his renowned debut album, Reasonable Doubt. This moment, when Tony is first drawn to the wealth and power of the narcotics trade, poetically coincides with Jay-Z’s rapid emergence as a megastar in the rap genre and business mogul. An equally essential and revered debut album from another New York-based rapper, Illmatic by Nas, features the single, “The World Is Yours.” The track, with a title inspired by the mantra that Tony memorializes in his palace and a music video that shows Nas sitting in a hot tub like the kingpin, is an explicit homage to the film. As long as it was configured into a rhyme, Jay-Z and Nas, who would later feud in the 2000s, agreed on the seismic resonance of Scarface. Both were never shy to allude to the film throughout their vast discographies.

Scarface is so embedded in hip-hop vernacular that listing every allusion to the film in songs of the genre would be an eternal exercise. The Notorious B.I.G. took a liking to the film, reciting Frank Lopez’s (Robert Loggia) well-suited advice to never get high on your own supply in his track, “Ten Crack Commandments.” “Livin’ Fat,” the track by Fat Joe, opens with a sample of Tony proclaiming, “We got to think big, now.” One thing is for sure, the admiration for Scarface is never cryptic throughout the evolution of hip-hop. A 2011 Future track was titled, “Tony Montana.” The cultural touchstone of the film, now 40 years old, is passed down from generation to generation in rap, with artists such as Meek Mill and Migos taking the mantle.

The reality that a film by the person who directed Carrie and Blow Out becoming an omnipresent cultural fixture in hip-hop is baffling. How did this manifest? While De Palma is not quite a satirical filmmaker, his themes and ideas are conveyed with an ironic, acerbic edge. He takes comfort in subversion and exposes the rotten core of people and establishments. As the subject of De Palma, a documentary of the director’s life work by Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow, he speculated that Scarface was poorly received because the critical body interpreted it as an attack on the Hollywood apparatus. De Palma’s direction of Scarface counters Oliver Stone’s political hand-wringing and the disillusionment of the American Dream, and this conflict manifests on screen. The hip-hop community has seemingly approached the film’s text sincerely — evolving as gospel for artists of the genre. In their eyes, Scarface is not merely De Palma’s genre exercise of converging trashy B-movie elements with the austerity of classic gangster films. Inadvertently, the film spoke to the palpable soul of hip-hop.

An unmistakable trait of hip-hop, especially in the ’90s, is the collective framing of a rags-to-riches story regarding individual artists and the genre as a whole. As Nas describes in a bonus featurette on the film’s 20th anniversary DVD, “We all are savages in pursuit of the American Dream. Rappers relate to that ’cause that’s how we come up.” Scarface, in a brutal fashion, clearly expresses this arc. The story of the most iconic rappers in history is not much different. They were molded by the tough neighborhoods of their upbringing, uncharacteristically broke into the music business with their innate talents, and attained wealth and fame instantaneously. Andre 3000 of Outkast cites Tony Montana as a maverick anti-hero. He is vicious, but since he came from nothing, you can’t help but root for him.

Because of the inherent autobiographical qualities in hip-hop, any media that embodies the heart and soul of the genre is bound to strike a kinship. Aided by De Palma’s maximalist direction and Stone’s punchy dialogue, the candidness of rap is equally represented on celluloid. The sweat-inducing threat of violence in the drug trade, the hustling for cash, and the hostility stemming from upholding prideful masculinity that Scarface presents is not sensational genre fare for the hip-hop community like how most audiences consumed it in 1983. This story, at least metaphorically, was them. Hip-hop was a platform to flaunt success and wealth, and by proxy relieve pent-up frustration, as growing up a young African-American is burdensome in the face of being doubted and disrespected. From this viewpoint, Tony Montana’s gaudy exhibition of his wealth is not without tact. Founder of Def Jam Records Russell Simmons claims that Tony embodies “empowerment at all costs,” a mantra that has defined hip-hop since its inception.

The flip side of the hip-hop coin is its poignancy as a cautionary tale for the lifestyle of excess that numerous stars have succumbed to over the years. As Fat Joe states, as a rapper who indulges in greed, “You either get killed or go to jail if you live your life like that.” ’90s hip-hop is just as honest in celebration of fame and wealth as it is with the consequences of a life of debauchery. The cognizance shared among artists that their life in the fast lane features fatalistic consequences is part of the genre’s alluring complex. Striving to have the proverbial world in your palms was the only feasible way for Tony Montana to live in America. Tony’s arc mirrors the natural progression of a young Black man growing up in poverty to suddenly amassing an extraordinary amount of wealth. The glamour of fame and success that the ’90s hip-hop boom was not for the faint of heart.

Brian De Palma revealed in the eponymous documentary that he was unaware of Scarface‘s widespread influence on hip-hop until he was informed by an executive years later. Vying to cash in on this trend, De Palma was requested by Universal to replace Giorgio Moroder‘s synthesizer score with a new cut of the film that integrated a hip-hop soundtrack, but he swiftly declined. Al Pacino expressed gratitude for the hip-hop community’s revival of Scarface, saying that “they really get it, and they understand it.” Connecting with audiences requires plenty of luck in the film industry. Scarface struck gold with the ripe and passionate hip-hop community after being initially abandoned by audiences. In essence, this was a rags-to-riches story of its own.