The Big Picture

- Oppenheimer focuses on the man himself, rather than the bombings, highlighting the intense control he had over the Manhattan Project.

- The film suggests that Oppenheimer’s guilt was partially self-serving, as he tries to seek redemption for his actions.

- The decision to not show the bombings themselves adds greater impact and condemnation to Oppenheimer’s inability to face the horrors he helped create.

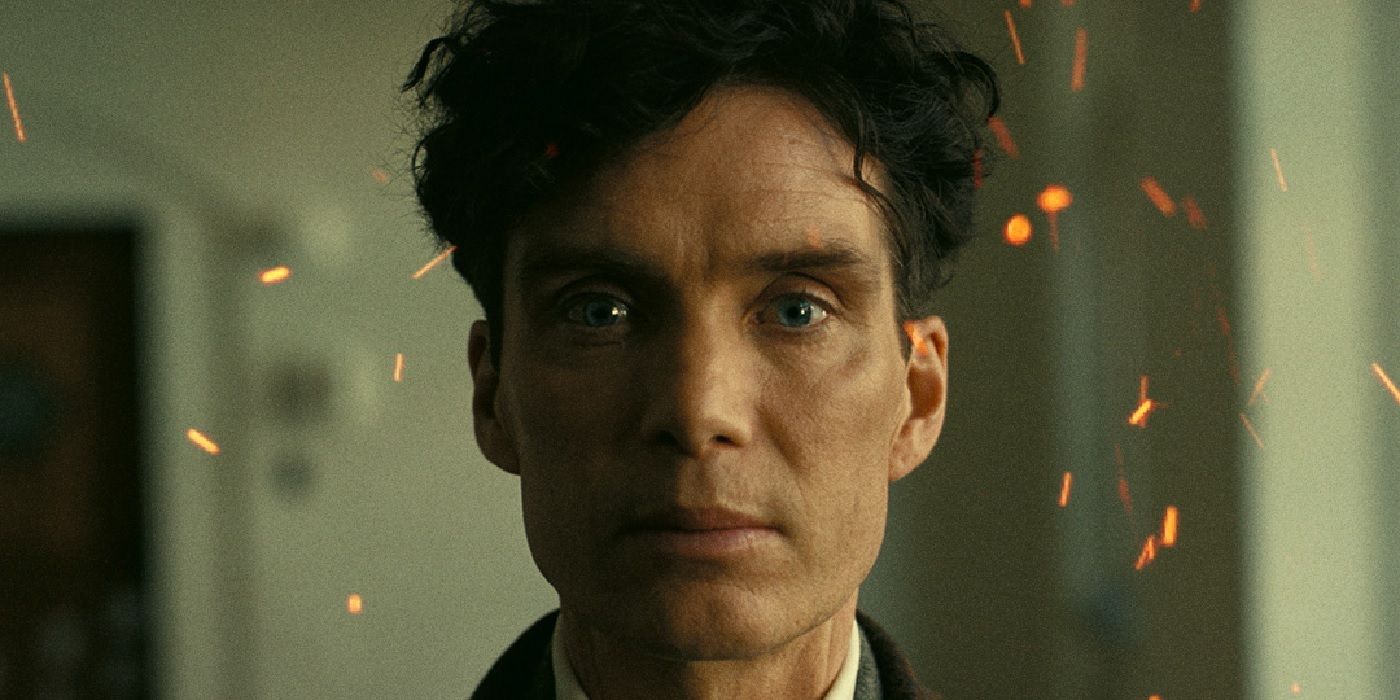

Christopher Nolan‘s Golden Globe-winning film about the “father of the atomic bomb,” Oppenheimer, follows J. Robert Oppenheimer (brilliantly played by Cillian Murphy) from his beginnings in academia through the Manhattan Project, culminating in a dramatic fall from grace engineered by government bureaucrats when he starts speaking out against his most famous invention. Based on an 800-page, Pulitzer-winning biography called American Prometheus, Oppenheimer is scrupulous in its detail: care is taken to avoid composite characters, and everything from a New Mexico camping trip to an impulsive apple poisoning is included.It has everything, in fact, but the bombings themselves. Nolan shows the first test in an awe-inspiring set piece; he shows us the political sausage-making ahead of the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as the toll the attack takes on Oppenheimer’s psyche; he even shows us the horrific effects of the bomb in one of Oppenheimer’s nightmarish, stress-induced hallucinations, depicting the flesh melting off of a woman’s body before Oppenheimer steps over a charred carcass. But Nolan never shows us the Enola Gay dropping its payload, or the quiet summer days shattered by the terrifying new weapon. Instead, we see Oppenheimer awake in the small hours of the morning, waiting for the speech from Harry S. Truman, which declared that the United States “spent $2 billion on the greatest scientific gamble in history — and won.”

Oppenheimer

The story of American scientist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and his role in the development of the atomic bomb.

- Release Date

- July 21, 2023

- Rating

- R

- Runtime

- 181

- Genres

- War , Biography , Drama

Christopher Nolan’s ‘Oppenheimer’ Stresses the Scientist’s Distance From the Violence

To some, this may seem like an egregious oversight. While a pop culture website is no place to hash out the ethics of nuclear warfare, the bombing of civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was undeniably barbaric. Even if it was necessary to save the lives of millions in a more conventional invasion (which is debatable), it was an act of staggering violence that, as with the Trail of Tears and Abu Ghraib, every American citizen must come to terms with. Clothing patterns were seared into the skin, for crying out loud — should the guilt of the white guy who invented the bomb be given more weight than the hundreds of thousands who died in agony?

The answer, of course, is no. But the interesting thing about Oppenheimer, and part of what makes it an all-time great biopic, is that it doesn’t suggest otherwise. In fact, that sense of removal from the carnage is part of the film’s whole point. There’s a reason why the film is called Oppenheimer, rather than American Prometheus or Destroyer of Worlds or something: it is intensely focused on the man himself, to the point where much of the script is written in the first person. Rather than “Oppenheimer walks across the room,” it might read “I walk across the room” — an unorthodox approach for a screenplay, to say the least. As the leader of the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, he is in full control of what happens: he makes personnel decisions, steers the project in one direction or another, and asserts himself with confidence against brusque military man Leslie Groves (Matt Damon). Like some combination of a mayor and a conductor, Oppenheimer shepherds the bomb to a successful test — and then begins to learn just how little control he has over his invention.

Fat Man and Little Boy are loaded into a military convoy, and Oppenheimer asks Groves (who has proven himself to be a staunch, if grouchy, ally) if he’ll be needed in Washington. “Why?” Groves responds, and what stings is that it’s a genuine question: as far as the military is concerned, the scientist’s work is done. While Oppenheimer does end up in a Cabinet meeting ahead of the attacks, his input is limited, and the discussion of possible targets reveals how capricious the whole enterprise really is: Secretary of War Henry Stimson (James Remar) spares the city of Kyoto because he went on a honeymoon there with his wife. (This is admittedly not entirely true — Stimson feared the galvanizing effect an attack on such a culturally important city might have on the Japanese, but it’s a disquieting example of America’s thoughtless power all the same.)

‘Oppenheimer’s Composer Implemented a “New Recording Technique” for Film

Ludwig Göransson came up with a new strategy to hit the atomic notes required.

Oppenheimer’s Guilt Was Partially Self-Serving

The bombings occur, and because Oppenheimer doesn’t see them, we don’t see them. We see his inner turmoil, certainly, but he has no inside information at this point: as Nolan points out, he’s in the same boat as the average civilian at home. When Oppenheimer approaches President Truman (Gary Oldman) with concerns that he has “blood on his hands,” Truman responds with scorn. “Do you think the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki give a shit who made the bomb?” he sneers, before dismissing the scientist as a “crybaby.” It’s shockingly callous, but further illustrates Oppenheimer’s diminishing power while also pointing towards another potent theme: guilt, consequences, and how much (or how little) they really matter.

Oppenheimer has plenty to feel guilty about, even before he successfully tests the atomic bomb: his love affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) leads to her death, whether by suicide or homicide, and his work on the Manhattan Project makes him an absent husband for his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt). By the time the bomb is made and the U.S. military makes use of it, he’s a haunted husk of a man, gaunt and distant with a thousand-yard stare. He tries to tell anyone who will listen about the dangers of the hydrogen bomb and nuclear proliferation, and it’s clear that he sincerely believes what he’s saying. But there’s a self-serving element to his public penance, as well, which both Kitty and Oppenheimer’s nemesis Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) point out. “You don’t get to commit the sin and have the rest of us feel sorry for you for there being consequences,” Kitty tells Oppenheimer; she’s speaking in the context of her husband’s affair with Tatlock, but it rings true for the creation of the bomb, as well.

There is only one point in the movie where Oppenheimer is directly faced with the horrors of the nuclear bomb. Unseen to the audience, a presenter goes through slides of photographs taken in the aftermath of Hiroshima, showing an auditorium of people (including Oppenheimer) the effects of firestorms and radiation poisoning. And despite his lamentations, despite his hand-wringing, despite his genuine fear for the future of humanity, Oppenheimer can’t bring himself to look. This one moment is more impactful — and more damning — than any dutiful depiction of an atrocity would be.

Oppenheimer is available to rent on Amazon Prime Video in the U.S. and will be available to stream on Peacock in the U.S. on February 16.

Rent on Amazon