The Big Picture

- Saltburn is a divisive film, with some praising its art direction and performances, while others find it style over substance.

- The movie explores the class divide and presents a “eat the rich” message, but its execution becomes confusing.

- Director Emerald Fennell has a strong aesthetic and a desire to say something important, but the film’s message about class is mishandled and lacks nuance.

What has surprisingly proven to be one of the most divisive films of the year is Saltburn. Some love it and commend Emerald Fennell‘s latest for its art direction, twisty narrative, and the performances at its core. Others, myself included, have found the film to be style over substance, presenting an undeniably strong aesthetic, but with little else being brought to the table. In a technical sense, there isn’t really anything that you can complain about with Saltburn. However, there is clearly a deep desire from Fennell to say something important and progressive; such was the case with Promising Young Woman. There is an attempt to try and present lofty, thought-provoking ideas, but it’s how Fennell tries to execute them that makes things confusing.

Saltburn

A student at Oxford University finds himself drawn into the world of a charming and aristocratic classmate, who invites him to his eccentric family’s sprawling estate for a summer never to be forgotten.

- Release Date

- November 17, 2023

- Director

- Emerald Fennell

- Cast

- Rosamund Pike, Barry Keoghan, Jacob Elordi, Carey Mulligan, Archie Madekwe

- Rating

- R

- Runtime

- 127 minutes

- Main Genre

- Drama

Saltburn has two dueling narratives at its core. One is apparent very early on, that being an “eat the rich” message. The wealthy family who we spend the entire narrative with are air-headed, pompous elitists who know nothing but their own, very limited point of view, and seem to have no desire to understand anything outside of it. We root for Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) for a large chunk of the movie, a seemingly lonely student who is on scholarship at Oxford and is given the chance to hang out with a family of a class well above his own. It is only over time that there are undercurrents of Fennell fearing those who “have not.” Quick’s motives come to the surface and we almost start to feel sorry for this financially loaded family who we once couldn’t stand. Does Fennell despise the rich? Is she trying to present a message in the same vein as The Menu and Parasite. But then Saltburn takes a hard turn and makes us wonder why we ever sided with Quick and against the rich in the first place. You looked cool for a little while, but what are you really trying to say, Saltburn?

‘Saltburn’ Could Have Been a Great Psychological Thriller

It’s always fun when a mid-budget movie sneaks up on everyone and causes a huge ruckus. Such is the case with Saltburn, a follow-up to one of the best directorial debuts in years that had film fans everywhere debating ad nauseam. If you haven’t seen this movie yet but are interested, then you’d better back out now. While Saltburn is by no means perfect, it’s still a fun one to experience knowing as little as possible. Its story is set in 2006 and follows Oliver Quick, a sheepish scholarship student at Oxford University who quickly becomes infatuated with his well-liked, well-off, good-looking peer, Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi). After Oliver and Felix quickly become friends, Felix invites him to stay for the summer at his family’s behemoth of a countryside estate, the idyllic Saltburn. It doesn’t take long for things to take a sinister turn, though, or for our faith in Oliver to wane. As it turns out, he’s a sociopathic, manipulative monster who planned every bit of the Catton family’s downfall far in advance.

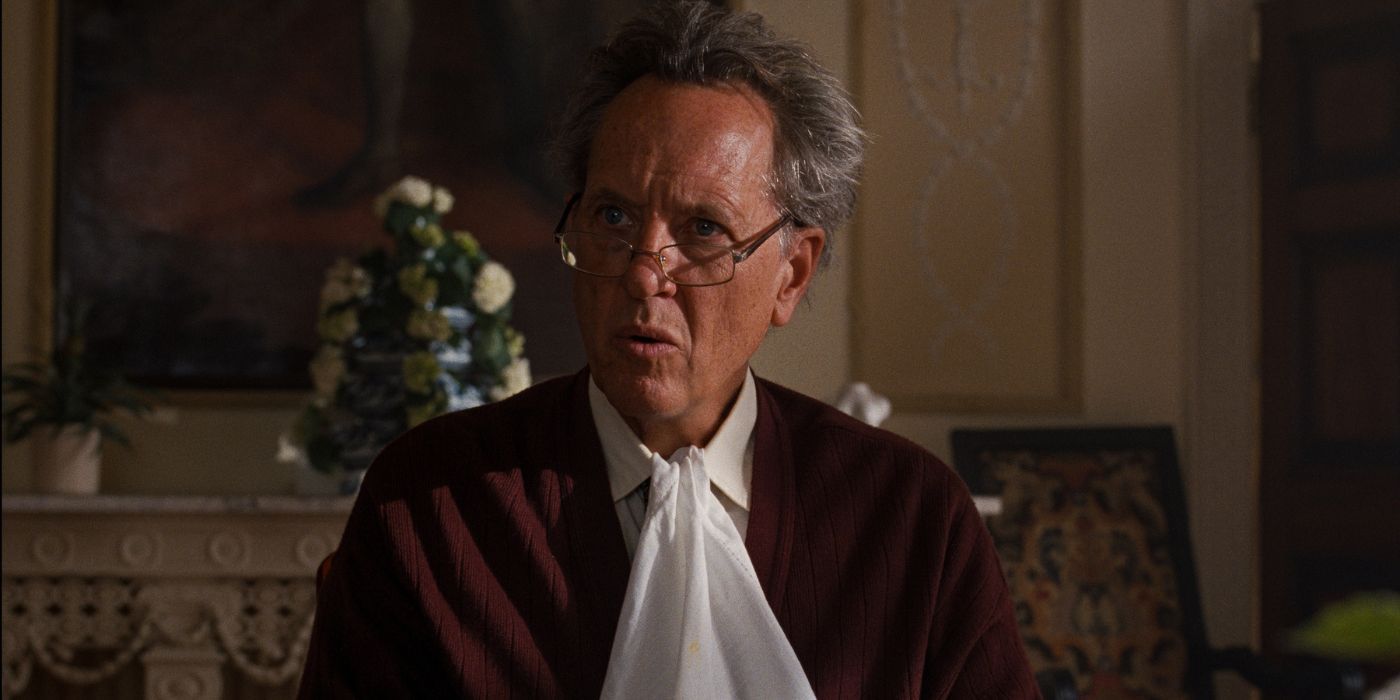

Is Saltburn an artistic masterpiece? Or is it a misguided attempt at class commentary? There is no clear critical consensus on these questions… nor is there a concrete answer as to what this movie wants to say. One thing is for sure, and that is that Saltburn is a headache. As the movie kicks off, we’re made to feel sorry for Oliver and hope to see him succeed in his time at Oxford. Things only get better when he befriends Felix, the only member of the Catton family who seems neither ill-intended nor brainless. Everyone else who resides at the Catton estate bears one of these two traits. His cousin Farleigh (Archie Madekwe) seems to be out to get Oliver at every turn and sister Venetia (Alison Oliver) sees Oliver as nothing but a new toy to play with and manipulate. Felix’s parents (played by Rosamund Pike and Richard E. Grant, the best parts of this movie) are about as detached from everyday life as you might expect from a bunch of one-percenters. Felix’s parents aren’t all that nauseating (they’re actually hilarious), but when coupled with his cousin and sister, you can’t help but roll your eyes at the whole bunch. Fennell starts out clearly painting the rich as the villains, before fumbling the entire message of this movie in the final stretch.

But let’s take a minute and look at why Fennell portrays the rich this way. If you know anything about her or the current up-and-coming generation of exciting filmmakers, you know that Emerald Fennell has made quite a name for herself in the last few years. She directed the COVID-hit, Promising Young Woman, went on to win the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay (as well as nominations for Best Director and Picture), and secured what had to be a decent enough budget to pull off a movie as miraculously crafted as Saltburn. This is a big, beautifully shot movie with a stacked cast. Fennell has a serious pull in the movie game, so she can’t be struggling that badly.

‘Saltburn’ Director Emerald Fennell Is “Definitely” Planning to Make a Horror Movie

The ‘Promising Young Woman’ helmer also shares her favorite episode of ‘Are You Afraid of the Dark?’

Not to mention, her background isn’t exactly the most humble either. Fennell went to one of the UK’s most expensive private schools, before attending Oxford (pulling from her experience from Saltburn). So, is Fennell going after her own people here? There has been a recent string of world-famous filmmakers who have their eyes set on taking down the elite. Bong Joon-ho did so masterfully in Parasite, Rian Johnson is still having fun with the Knives Out series, and Ruben Östlund jumped on the bandwagon with Triangle of Sadness, winning the Palme d’Or in the process. So, Fennell is by no means the first middle to upper-class person to make a film about the class divide. But when its approach is as mishandled as this, the economic background of the director/writer does play a part. British cinema has no shortage of films that bring nuance to the class conversation; Mike Leigh and Ken Loach have built impressive careers upon this subgenre. While this is an issue sweeping the entire film industry, Saltburn is another example of a story being told by the wrong person.

Is ‘Saltburn’ Painting the Poor as Monsters?

The strangest thing about all of this comes towards the end of the second act when it’s revealed that Oliver has been behind everything sinister at Saltburn. Suddenly, the Cattons are made out to be the victims. Oliver is painted to be a total sociopath and spends the rest of the movie unraveling his entire plan to kill off Felix’s family, inherit their wealth, and take over Saltburn. So for the last 45 minutes or so, Fennell spins an awfully aporophobic web, one that feels like a bureaucrat clutching their Rolex and nailing their mansion’s doors shut when they walk past a homeless person. It’s as if old fears of letting those without be trudged up and thrown on screen. For someone who clearly has a desire to be seen as a progressive artist, why on Earth would you take a platform as big as a movie to paint poor and middle-class people as monsters? Does she relate to Felix and think that his kindness makes this all go down easier? It doesn’t matter how you package this because any way you roll it, there’s an apparent hostility towards anyone outside the elite. Yes, it’s revealed that Oliver isn’t as poor as he tried to come off; he comes from a happy family and indeed had money to pay for a round of drinks but wanted Felix to offer to bring them closer. But still, compared to Felix, Oliver is miles below in the food chain.

However, Oliver’s ultimate victory (if you want to call it that) in taking over Saltburn could also be seen as just that — a victory. He has, for lack of a better word, “eaten the rich” and acquired their wealth for himself. For a little over the first half of the movie, the audience is made to root for Oliver’s success in breaking out of his shell and fitting in with these people. That said, how are we supposed to stomach the ends? They definitely don’t justify the means. Oliver becomes so evil in the second half that it’s impossible to root for him. We might not like the Cattons, but I doubt that anyone hoped to see all of them brutally killed. So yeah, Oliver “ate the rich”… but are we supposed to be happy about it? Fennell never makes any of this clear.

‘Saltburn’ is an Aesthetic Wonder, Yet a Criminally Muddied Vision

Saltburn just needed to spend more time cooking. The cinematography, soundtrack, set design, performances, and direction are all fantastic here — there’s no denying that. It just feels like Fennell was more interested in making this type of movie, one that is both a dark comedy and a psychological thriller, set in a beautiful location with pop and baroque needle drops. If she left it at that and purely provided a fun and riveting movie-going experience, then that would be wonderful. There’s nothing wrong with movies being that simple. But if you’re making a piece of art that is trying to say something about our society, the wealth gap, and the deranged ways that different classes treat each other, then you have to give it more time before calling “action.” These movies can’t be haphazardly thrown together. When they are, you end up with a thematic tug-of-war like Saltburn that clearly has no idea what it really wants to say.

Aesthetically driven films are a necessity so that we can have a wide variety in what we watch. Not every film needs to be steeped in intricate plot devices, full of rich character moments, or riddled with lofty themes. But if you’re going to go after big ideas, then you better do it with some sort of nuance. Saltburn could have been so much more. Does it want us to hate the rich? Is it afraid of the poor? If Fennell spent more time figuring out these ideas, she might not have ended up with such a frustrating result.

Saltburn is now playing in theaters.

Buy Tickets Now