The Big Picture

- The Prince of Egypt composer Stephen Schwartz drew inspiration from the original animated film and conducted extensive research on the musical’s cultural setting to create an authentic sound.

- Schwartz discusses the depth he and the creative team aimed to achieve in the relationship between Moses and Ramesses in the stage adaptation, and how it impacted the reworking of the song “The Plagues.”

- Schwartz says that he could not have anticipated how popular Wicked would be 20 years later, and says it remains relevant to this day.

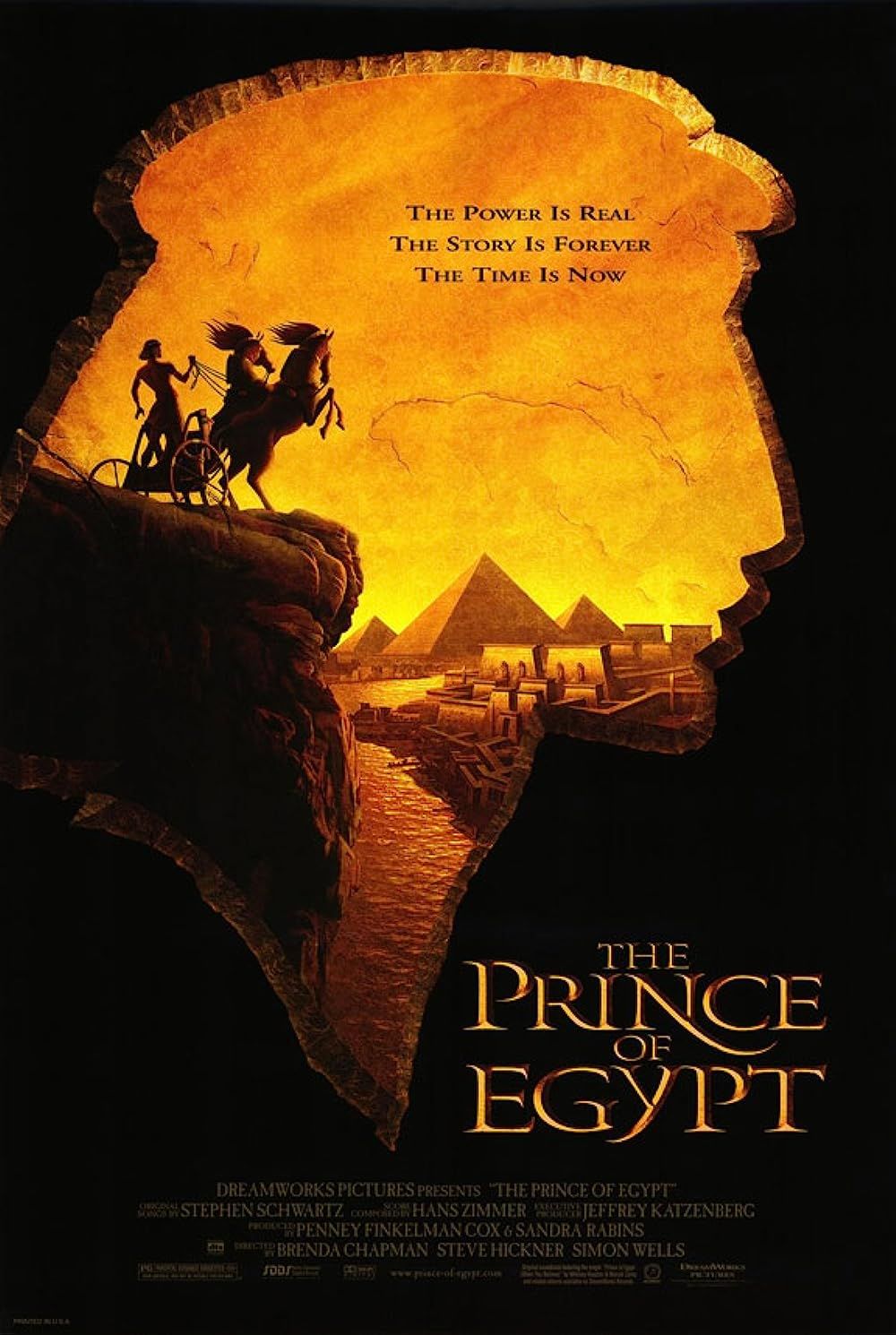

In 2020, The Prince of Egypt: The Musical opened on London’s West End, based on the animated movie of the same name, and featuring new music and lyrics from composer Stephen Schwartz, whose work on the stage and screen also includes Godspell, Wicked, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, and Enchanted. Unfortunately, the rise of the COVID-19 pandemic forced the show to close for over a year before reopening in the summer of 2021. Fortunately for fans of the musical and the original animated film, however, the production was filmed and had a limited theatrical run this past October, and is available on Digital now.

Up next, Schwartz is returning to the land of Oz for the two-part movie adaptation of Wicked from director Jon M. Chu, which stars Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba, Ariana Grande as Glinda, and Jonathan Bailey as Fiyero. The films are expected to premiere in 2024 and 2025 respectively, during the holiday season, and boast a massive all-star supporting cast.

In this one-on-one interview with Collider’s Arezou Amin, Schwartz talks about revisiting The Prince of Egypt over two decades later for the stage adaptation, and what inspired the changes to Moses and Ramesses’ dynamic. He also talks about why Broadway-style music works so well in animated movies, and talks about the enduring legacy of Wicked. He also talked about returning for Wicked, and the differences in adapting stage-to-screen and vice-versa. Read on for the full transcript.

COLLIDER: So, the stage version of The Prince of Egypt just had its theatrical run, recorded a few years ago. All the same, what was it like revisiting this project all these years later and having to adapt it to the stage? Was it challenging to get back into that headspace?

STEPHEN SCHWARTZ: It was fun. It wasn’t really challenging to get back into the headspace. For me, as the composer, involved with the musical sound, it meant my going back to the research I had done originally for the animated feature. I listened to a lot of music of the area, of the region and the culture, so I listened to Hebraic lullabies and Middle Eastern instrumental music featuring the particular instrumentation. I found a recording that purported to be of ancient Egyptian court music, though how they possibly knew what that sounded like, I don’t know. Even some pop tapes that I got on the streets of Cairo when we were visiting there, just to really get the flavor of the place. And so, I’ve done a lot of research, and I had it all still, obviously, so I went back and relistened and then talked with my orchestrator, August Eriksmoen, about trying to use some authentic instruments within the orchestra, particularly percussion instruments, to really try and have the show sound have that air of authenticity that we were able to achieve with the film.

Steven Spielberg Inspired This Change in the Musical

Within the film, because there are the songs from the movie, there’s all the new tracks for the show, one that really caught my attention, as somebody who has seen the movie more times than I would ever be able to count, was “The Plagues,” because it’s the hybrid of the old song and the new. I wanted to talk about that decision to kind of rework it. Was it because Moses and Ramesses’ interaction had changed slightly in the stage show? What went into that?

SCHWARTZ: That’s a good question. One of the things that we strove for, and we feel we were able to do in the stage musical because we had more time, was to go into more depth in terms of the relationship between Moses and Ramesses. This was originally conceived when the animated feature was being made. Steven Spielberg said, “I see this as a brother story,” the story of these two young men who’ve grown up together, who love each other, and then are forced by their destinies to become antagonists, and then if and how they can reconcile. So, that was something that we tried to do even more of and with more depth in the show, and of course, because you have more time and there are gonna be more songs, we were able to explore that more and just treat it as if we were writing a musical for the first time. Therefore, “The Plagues” allowed us to go into more depth with the relationship between Moses and Ramesses.

Broadening it out a little, not just with The Prince of Egypt, but with The Hunchback of Notre Dame, both of these soundtracks lend themselves so well, particularly, to this big Broadway sort of sound and scale. What is it about animation in particular that lends itself to that theatricality?

SCHWARTZ: Well, animation is the closest of the film media, or genres if you will, to stage because it’s very artificial. Let’s face it, it’s drawings. And theater is an artificial medium that requires the audience to suspend its disbelief because you can see that you’re not really in Egypt, and those aren’t really camels or whatever. It’s something where the audience’s imagination is complicit with the show itself, and that’s true in animation because we know we’re looking at drawings, or these days we know we’re looking at computer generated figures, and we agree that we’re going to treat this as real. But at the same time, you’re able to do very magical things both in animation and on the stage by using these kinds of theatrical devices. Live-action movies are all about looking as real as possible, making you believe, “I really am on Mars,” or, “I really am under the ocean,” or whatever. But animation and theater want you to use your imagination more.

So it helps with that suspension of disbelief essentially.

SCHWARTZ: Yes, exactly.

So, because we’re talking about Broadway, I would be extremely remiss if I didn’t ask you about Wicked because it’s celebrating 20 years this year, which I can’t quite believe.

SCHWARTZ: Isn’t that crazy?

It’s every creative’s hope, I guess, but did you ever conceive of it still being this big 20 years later?

SCHWARTZ: No, I mean, of course not. For one thing, when I started working in the musical theater, there was no such thing as shows which ran 20 years. So, if the show ran for five years, it was one of the biggest hits of all time. That obviously changed before Wicked opened because there was The Phantom of the Opera and there was The Lion King and the revival of Chicago, so there were a few shows that had the crazy forever runs, but one never expects that one’s own show is gonna join that list. What’s been nice about Wicked is how it seems to continue to have contemporary relevance for audiences. In some ways it’s unfortunate. Politically, it’s unfortunate. I wish it weren’t as relevant as it is. I sort of feel that way about Prince of Egypt, too. I wish it weren’t as relevant to what’s going on right now as it is, but they do speak to what’s happening in our world and I think that helps them to remain current.

I want to tie those two together in just a second, but – and I know you probably can’t say much – can you tease anything about working on the movie?

SCHWARTZ: Oh, I can tell you a lot. Most of it has been shot. We ultimately decided to do two movies because we couldn’t get it all crammed into one movie without, we felt, really compromising the story. We thought no one wanted to sit for four hours and see one movie [laughs], so it got divided into two movies. But yeah, most of it has been shot. The actors’ strike, of course, meant that they couldn’t quite finish. Now that that’s settled, they’ll finish the principal photography for that. But our director, Jon Chu, has been editing for months. I can tell you that it’s gonna sound great because I was in the studio working with these unbelievable singers. I mean, Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande are absolutely world-class great singers and great singing actresses, so I know those performances, vocally, are going to be amazing. And I was on set enough to see the astounding design, both the scenic design and the crazily brilliant costume design, so I’m assuming it’s gonna look great. That’s what I know so far.

Stephen Schwartz Says Adapting Stage-to-Screen Is Very Different From Screen-to-Stage

I personally can’t wait. I saw Wicked when I was 17 and that was it. I fell in love. So, tying it together with The Prince of Egypt, you’ve gone from film to stage and now you’re going from stage to film. I’m wondering whether the process of adapting in either direction has more in common or are they extremely different?

SCHWARTZ: They’re different, actually. Going from a film to stage, particularly a film to a stage musical, as I said, there’s an expansion in the amount of time you have and more of the story is told through song, through dance, than on film in general, at least in my experience. But going from stage to film, there are many, many things you can show that you can’t do on stage. On the other hand, it could be very, very effective in a stage musical simply to have one person stand in the middle of the stage and sing for three-and-a-half minutes – can’t do that in a movie. [Laughs] The camera has to be moving and, you know, what are you seeing while that’s going on? So, the whole way song is treated is different in film, and one has to keep that in mind.

Of course, with what’s happened with Prince of Egypt, basically that is a video recording, a film recording of the stage show. So, it’s both trying to give the audience who could not get to see it on stage or else saw it on stage and wanna remember it and see it again, to give the feeling of being in the theater, having the audience around you, having long shots so you see the entire beautiful stage pictures, but also having the advantage of being able to do close-ups, being able to take an angle from behind the actors or off to the side. It’s as if you could run around the theater and just be in all different seats, and run up on stage and look at the actors. You get more perspective of it than you would just seeing it in your own one seat in the theater, but this attempt is still to have the energy of a live theater performance.

You mentioned the difference between on stage when somebody is just there and singing and how it has to change once it’s on camera, so I just want to ask a bit more about that. What changes, from your perspective, would you make to something that would otherwise just be a spotlight solo performance?

SCHWARTZ: Well, you have to figure out, particularly if it’s a song that was written for stage, and now it’s going to be on film, how can it move? What can you see on the camera? Is a character taking a physical journey? Do you go into the character’s mind? Are you showing different perspectives? What do you do? As I’ve said, film is a much more literal medium than theater. The audience in theater is supplying a lot with their imagination, and in film it’s just you’re showing it. So the question is, what are you showing during these moments that were originally written to just have someone stand on stage and sing?

The Prince of Egypt: The Musical is available on Digital now from Universal Pictures Home Entertainment.

The Prince of Egypt

- Release Date

- December 16, 1998

- Director

- Brenda Chapman, Steve Hickner, Simon Wells

- Cast

- Val Kilmer, Ralph Fiennes, Michelle Pfeiffer, Sandra Bullock, Jeff Goldblum, Danny Glover

- Rating

- PG

- Runtime

- 99

- Main Genre

- Animation

- Genres

- Animation, Adventure, Documentary, Drama, Family, History, Musical

- Writers

- Philip LaZebnik, Nicholas Meyer

- Tagline

- Two brothers united by friendship divided by destiny.

Watch on Prime Video