The Big Picture

- The iconic scene in Jaws where Quint tells the story of surviving the sinking of the USS Indianapolis is based on a real event, adding a nightmarish element to the film’s final act.

- The USS Indianapolis sank in 1945, resulting in the greatest loss of life due to shark attacks in history. Quint’s monologue captures the grim reality of the incident.

- While some details in Quint’s speech are fictionalized for dramatic effect, much of it is historically accurate, making it a successful tribute to the real-life tragedy.

Few films contain as many iconic scenes as Jaws. From its opening which sees a young woman being attacked by an unseen creature after she goes skinny-dipping, all the way to its explosive finale which finds police chief Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) vanquishing the shark spectacularly, Jaws is 124 minutes of unbridled cinematic joy. While its troubled production almost brought Steven Spielberg’s career to an abrupt end due to his insistence on shooting at sea, its worldwide success which culminated in it becoming the highest-grossing film ever made would catalyze to thrust the young filmmaker into becoming cinema’s most famous director. It’s impressive that (despite what must have felt like an endless series of problems) he was still able to craft the definitive summer blockbuster and one that continues to attract significant critical attention.

Perhaps its most analyzed scene is also its simplest. After 90 minutes of carnage, mayhem, and more than enough haunting musical cues that’ll make anyone think twice about swimming in the ocean again, Spielberg decides to put the brakes on to allow for the film’s most quietly powerful moment.

Jaws (1975)

When a killer shark unleashes chaos on a beach community off Cape Cod, it’s up to a local sheriff, a marine biologist, and an old seafarer to hunt the beast down.

- Release Date

- June 20, 1975

- Runtime

- 124 Minutes

- Writers

- Peter Benchley , Carl Gottlieb

- Production Company

- Zanuck/Brown Company, Universal Pictures

How Does ‘Jaws’ Sets Up Its Final Act?

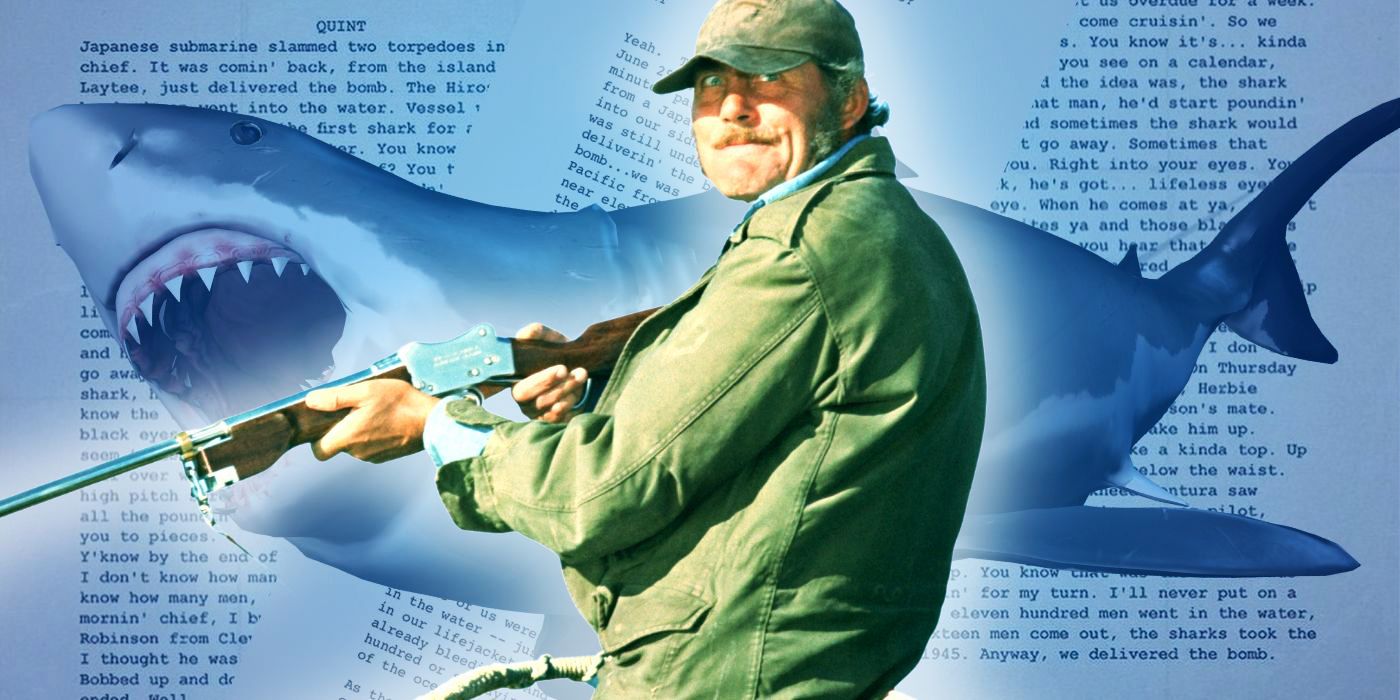

The scene in question sees Brody, oceanographer Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss), and shark hunter Sam Quint (Robert Shaw) taking a well-deserved rest around the solitary table onboard Quint’s ship, the Orca. While swapping stories about how they came to acquire their various scars, Quint descends into a monologue about his experiences while serving on the USS Indianapolis, a naval ship that sank during World War II. He recounts how he trod water for five days, battling hunger and frequent shark attacks before being rescued by a PBY aircraft. It’s a horrifying story that no one would emerge from unscathed – a notion Brody and Hooper are aware of after watching the drunken wreck before them suddenly transform into a far more tragic and tortured figure.

There’s a lot to dissect from his speech, and not just from the way it effortlessly sets a grim and foreboding tone going into the film’s final act – it’s also a scene that perfectly illustrates Spielberg’s “less is more” approach. It says a lot that the film’s most terrifying sequence is one where sharks appear only in a verbal rather than visual capacity. But it also helps that much of what Quint is saying is based on fact.

What Is the Terrifying Truth Behind Quint’s Story?

The USS Indianapolis was a real ship that sank in July 1945 following a secret mission in the Philippine Sea, and the immediate aftermath that left almost 900 people adrift in the ocean resulted in the greatest loss of life due to shark attacks in human history. This isn’t to say that everything in his monologue is real – even the most historically accurate films aren’t above embellishment for the sake of dramatic effect – but the cusp of his speech is surprisingly factual, making an already tense scene into something truly nightmarish.

Launched in November 1931, the Indianapolis played a central role in the Pacific War during the latter half of World War II, ultimately becoming one of the Navy’s flagship vessels until it was reassigned in 1945 as part of a top-secret mission. Its objective was to deliver a shipment of enriched uranium to Tinian island in the northwestern Pacific Ocean to aid in the construction of “Little Boy,” the atomic weapon that would be dropped on Hiroshima just a few weeks later. It departed San Francisco on July 16, hours after the controversial Trinity test that saw the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, and successfully delivered its cargo 10 days later. However, less than a week later it was hit by two Japanese torpedoes while en route to Leyte island in the Philippines. It took just 12 minutes to sink – 12 crucial minutes that claimed the lives of 300 of its 1,195 crew. Despite the lack of lifeboats and jackets, the survivors were forced to take their chances in the ocean, confident that rescue was on the horizon.

Only 316 men would survive the coming days, the rest killed by either exposure, dehydration, shark attacks, or worse. While a distress signal had been transmitted, none of the ships that received it did anything about it (one believed it to be a Japanese trap, while another had been ordered not to disturb its commanders). This meant only a routine flight by a PV-1 Ventura bomber three and a half days later resulted in the survivors being found. The lack of a response by the Navy despite knowing that the Indianapolis had failed to arrive in the Philippines on schedule was widely criticized, and substantial changes were made to ensure such a tragedy would never happen again. It also resulted in the controversial decision for the ship’s captain, Charles B. McVay III, to be court-martialed, making him the only United States captain to receive such a punishment during the war. While his record would later be cleared of all wrongdoing, this would only happen in 2001 – over 30 years after his death by suicide.

What Are the Origins of Quint’s Speech in ‘Jaws’?

While it was hardly a secret what had happened to the Indianapolis before Jaws, it wasn’t until the film’s release in 1975 that it became common knowledge. The origins of the speech come from Howard Sackler, a Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who worked as an uncredited writer on the film. Sackler was adamant about explaining Quint’s blind hatred for sharks and pitched the idea of making Quint a survivor of the disaster. Spielberg was receptive to his proposal, but after Sackler came back with just a single page of dialogue, it was left to another of the film’s uncredited writers, John Milius, to expand. Clearly, this was a job he took very seriously given that he came back with a 10-page soliloquy more fitting for a one-man stage production than a film – a concern Spielberg raised despite enjoying his work. In the end, it was Richard Shaw who had the last word, rewriting much of Milius’s contributions until he landed on the final version.

Which of the three writers deserves the most credit remains a matter of debate (although Spielberg has always referred to it as an equal collaboration), but it’s clear that somewhere along the line it morphed from being a history lesson into a speech befitting a fictional character in a movie. This probably explains why Quint tends to aggrandize the details even while adhering to the basic framework of what happened to the Indianapolis. The most egregious example is his insinuation that sharks were responsible for all the deaths after the ship sank. While many people did die as a result of shark attacks (potentially as high as 150), these still accounted for a relatively small number when compared to those who died from exposure or dehydration. This was likely an intentional mistake to strengthen Quint’s motivation, and while it did have the unfortunate consequence of adding to the misconceptions surrounding sharks (much like the entirety of Jaws), from a purely narrative perspective it serves the scene well.

What Isn’t True in ‘Jaws’?

Other sections aren’t true. Quint’s statement that no distress signal was sent is incorrect, as is the date he gives for when he was rescued (June 29, whereas the sinking of the real Indianapolis occurred a month later). There’s also no evidence that the “Herbie Robinson from Cleveland” whose half-eaten body he bumps into on Thursday morning existed, but given the sensitive nature of the event (which was still in living memory when Jaws released), it was a smart decision to avoid referencing real people. It’s also debatable if his “we delivered the bomb” line is accurate given that the weapon technically hadn’t been assembled yet, but such criticisms are probably too pedantic to get overly concerned with.

How Many ‘Jaws’ Movies Are There?

The ‘Jaws’ franchise has given us both some of the best and worst films ever made.

So not everything Quint says is factual, but trying to condense such a complex event into a few minutes of screen time was always going to necessitate changes. And even with this requirement, it’s impressive how accurate a lot of it is: the circumstances of how the Indianapolis sank, the reason why it was in the Pacific Ocean, the number of people who were rescued, and the horrific reason why many of them didn’t make it – that’s all true, and this adherent to historical fact makes it a far more successful tribute than some of its other cinematic portrayals (the Nicolas Cage film USS Indianapolis: Men of Courage springs to mind).

But putting this aside, it’s just a fantastic scene by itself. The way Quint commands the room with a few slurred words and the demeanor of someone already half buried by his demons, all the while Hooper stares on silently with an expression of pure horror – it’s brilliant stuff, and easily the greatest showcase of Shaw’s acting prowess. When viewed with the knowledge of its real-life basis, it’s his greatest showcase as a writer too.

Jaws is available to rent on Apple TV+ in the U.S.

Watch on Apple TV+