The Big Picture

- New Hollywood filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola captured America’s post-60s paranoia through psychological thrillers.

- ‘The Conversation’ weaved tech-savvy surveillance with moral dilemmas, mirroring society’s uncertainties.

- Coppola’s film blends repetition, obsession, and cynicism, painting a haunting portrait of personal and political paranoia.

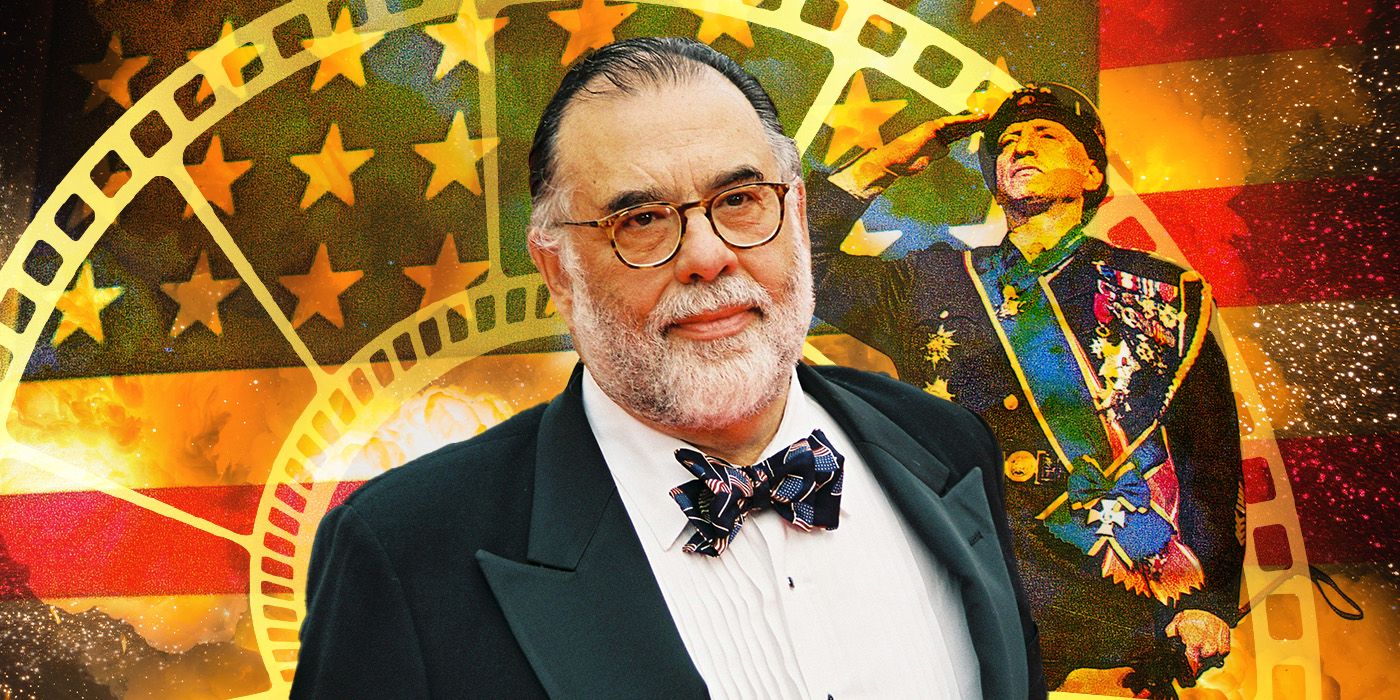

In the 1970s, Americans carried the burden of impending doom. Following the political and social upheaval of the late 1960s, the spirit of the United States was spiraling into the abyss. At the start of the decade, due to the lingering shadow of the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal/cover-up, paranoia upended liberty and justice as the defining trait of the country. Films, thanks to a radical new wave entering the mainstream, quickly responded to the national psyche with a new subgenre of psychological dramas known as the paranoid thriller. To be properly initiated into New Hollywood, a filmmaker must interpret the state of domestic affairs with unflinching cynicism and doubt, which was most disturbingly exemplified by The Conversation, the film that further cemented the legacy of Francis Ford Coppola and calcified the ’70s as the era of paranoia.

The Conversation

A paranoid, secretive surveillance expert has a crisis of conscience when he suspects that the couple he is spying on will be murdered.

- Release Date

- April 7, 1974

- Director

- Francis Ford Coppola

- Cast

- Gene Hackman , John Cazale , Allen Garfield , Frederic Forrest , Cindy Williams , Michael Higgins

- Runtime

- 113

New Hollywood Filmmakers Brought Paranoia to the Big Screen in the 1970s

The emergence of New Hollywood, the anti-establishment wave of filmmaking that formulated in the late ’60s and early ’70s, was no coincidence, as the first generation to embrace the opportunities of film school entered the industry at a vulnerable period. Influential filmmakers that are still relevant today, including Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma, and George Lucas, worked within the system and redefined the authorship of film. The current cinematic landscape of the time, notably hindered by bloated musicals with pastiche set pieces, did not reflect the American climate more accurately portrayed on the nightly news, which depicted ground-level footage of combat in the Vietnam jungle and anti-war protests in the streets. 1967, which saw the release of Bonnie and Clyde and The Graduate, changed everything. From there on out, mainstream films were not only going to reflect the current American malaise and dystopia, they were going to push the formalism of the art form.

After you direct The Godfather, one could reasonably expect complete creative autonomy, and the freedom to choose any project he desired was what Coppola received. The behind-the-scenes chaos of The Godfather nearly broke his spirit, but Coppola proved everyone wrong and created an undeniable masterpiece. Unlike The Godfather, which was preexisting material that he was reluctant to pursue, The Conversation was one from the heart. According to Coppola, the film “is a personal film based on my own original screenplay; it represents a personal direction I wanted my career to take.” The film was an original script that he had written in the mid-60s, an homage to the Italian expressionist cinema of the period, notably Michelangelo Antonioni‘s Blowup. At the Academy Awards held in 1975, Coppola was competing against himself, as both The Conversation and The Godfather Part II were nominated for Best Picture. While the continuation of Michael Corleone’s (Al Pacino) story took home the top prize at the Oscars, The Conversation won the Palme d’Or, the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Francis Ford Coppola Blends Autobiographical Storytelling With Paranoid Thrills in ‘The Conversation’

In the recent Coppola biography, The Path to Paradise, author Sam Wasson tracks Coppola’s rise as an artistic and technical entrepreneur with the founding of his production company, American Zoetrope. Coppola cultivated a farm system of aspiring creative talent and pushed the boundaries of the film medium, which included advancement in digital photography. Even during his youth, Coppola loved experimenting with cutting-edge technology, and this passion sprouted during his venture into filmmaking, where he developed breakthroughs in sound mixing with his collaborator, Walter Murch. The filmmaker’s background suggests that The Conversation‘s protagonist, Harry Caul (Gene Hackman), a tech-savvy contract surveillance operator who spies on people for clients, is close to an on-screen avatar for Coppola.

For Caul, voyeurism is pure labor — little to no paranoia is attached at all. Similar to the depiction of professional assassins that we see in movies, Caul has no sentimental attachment to his targets. He captures the conversations of his targets through illicit means and sends the tape to his client. The Conversation exists in a world where surveillance is commonplace. The high-tech devices that supply this behavior are even celebrated at an expo that Caul attends. Caul and his wiretapping partners aren’t as much a band of outlaws but mere co-workers. Like all totemic paranoid thrillers, the tension escalates at a steady pace, but the exterior of The Conversation suggests a mundanity to the act of spying. For Caul, his calculated lifestyle and emotional stasis crumble once he starts to care about the livelihood of his target.

The crux of the film revolves around a moral dilemma that Caul must confront. The film begins with Caul and his colleague, Stan (John Cazale) wiretapping a couple, Mark (Frederic Forrest) and Ann (Cindy Williams), walking through Union Square in San Francisco. After cleaning up the cacophonous sounds in his recording, he discovers that Mark said, “He’d kill us if he got the chance.” Or, at least, we think Caul discovered this breakthrough in the recording. The film never makes explicit statements or judgments about its characters and circumstances. In this case, Coppola tells the story through Call’s inscrutable mind, which comfortably leaves the truth behind what was said ambiguously. At the end of the film, Caul realizes that his interpretation of the muddled audio was misleading, as it’s revealed that Mark and Ann were not victims, but rather, part of a conspiracy to kill The Director (Robert Duvall), the man who hired Caul.

Francis Ford Coppola Was Fired For Writing One of His Most Famous Scenes

One might say he refused to cooperate.

Francis Ford Coppola Examines Obsessive Paranoia in ‘The Conversation’

Coppola, in an interview with GQ, said he was “interested in this idea that you’d make a movie in which repetition was an element. In other words, the same thing was being said over and over, but every time you heard it, it meant something a little different.” This provides rich commentary on paranoia as an emotional burden and not just a sensation created by domineering political and corporate forces. Caul’s paranoia, as he becomes fixated on his recording, devolves into obsession. “Harry’s punishment for his sins, be they real sins or not, is that he becomes obsessed, and he’s being gazed into,” Coppola said. Throw in Caul’s Catholic faith, and all the guilt and repentance associated with its teachings, and we leave the film with Caul as a broken man. The film’s closing moment is a haunting sequence executed with a surprising level of reservedness. Caul, devoid of any manic behavior, methodically tears down the walls of his apartment and calmly plays the saxophone inside his wrecked home.

Caul’s client, led by the ominously named “The Director” and his assistant, Martin Stett (a young Harrison Ford), is believed to be a corporation, but they might as well stand in for the central government. The specifics of their enterprise are purposefully left ambiguous, as all we need to know is that they are involved in nefarious affairs. The mystery surrounding Caul’s client speaks to the foreboding presence associated with the government in a post-Vietnam/Watergate American panic. Coppola never bothers to conceal the threatening aura of The Director’s business. By doing this, he provokes the audience into rooting for Caul as he breaks out of his timid shell and takes a moral objection to his client’s practices, which presumably involve the murder of his wife for her adultery. When Caul’s conscience is awakened, Coppola’s cynical interpretation of the paranoid thriller genre manifests. Caring about the safety of his wiretapping targets was the worst thing for the stability of this mental psyche. Much like the walls of his apartment that were shredded to pieces, the film leaves Caul as a shell of a man.

Other paranoid thrillers of the 1970s, including The Parallax View, Three Days of the Condor, and Marathon Man, are exceptionally well-crafted and perfectly calibrated to the tone of the contemporary American psyche. To translate it into modernized lingo, The Conversation operates as an “elevated” paranoid thriller, one that deploys its visceral genre tactics while simultaneously reflecting on the perverse nature of its thematic trends. In the middle of an iconic run of movies, Francis Ford Coppola combined his distinct vision with a topical national phenomenon to create a film that paints a clear portrait of the era. Even for those like Harry Caul who pivot and use their skills and advanced technological apparatus for good, one’s fate will succumb to the malpractices of our most “trusted” figures in power.

The Conversation is available to rent on Prime Video in the U.S.

Rent on Prime Video