The Big Picture

- Titane is a disgustingly gory film that invites viewers to identify with a serial murderer and confronts them with body horror in a lucid-dream-like atmosphere.

- The movie explores the transformative power of familial love, challenging its viewers to find humanity in the most unlikely places, even in the midst of violence and carnage.

- Alexia, the film’s protagonist, starts off as a monster fixated on machines but experiences a change in outlook when she encounters genuine paternal love, ultimately breaking free from her fixation with cars and embracing her own humanity.

Titane is a truly disgusting film in the best possible way. It’s fugue-like, gory, and brimming with Cronenbergian body horror that mixes flesh and metal into a pulsing mass for the audience to gawk (or gag) at in horror. The film takes great pride in being disgusting, inviting viewers to identify with the unsympathetic serial murderer Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) and stare in shock at the carnage left in her wake. Titane is draped head to toe in a lucid-dream-like atmosphere, where it is both perfectly ordinary and utterly absurd, dialectically suggesting that this is a version of reality that is both recognizably normal and also a world where someone could give birth to a human-car hybrid. It’s no surprise that Titane comes from the same mind as the cannibalistic film, Raw – French director and screenwriter Julia Ducournau, who is incredibly adept at making viscerally gross horror films that also, somehow, have a great deal of kindness and wholesomeness to them. Titane, for as bloody, sadistic, and downright nasty as it is, largely is a film about finding your own humanity and learning the value of intimate relationships (platonic, romantic, familial, etc.) with other people. While it begins with flippant, unflinching violence, it ends circling a sincere relationship between a very strange woman, and a grieving father, asserting the transformative power of familial love.

What Is ‘Titane’ About?

Titane follows the murderous exploits of showgirl Alexia, who works at a motor show. Her interest in cars goes beyond a casual appreciation or even obsession into absolute infatuation. The film partially revolves around a sexual encounter with a Cadillac resulting in Alexia becoming pregnant with… something. Is it a Pixar-style car? Is it a human child? A grisly mash-up of the two? We’re not quite sure what’s growing inside her until the end of the film, but we can see her stomach swelling as the story skips onward. Alexia is described by Ducournau as a character of the death drive, a repetitive compulsion towards destruction and violence. Particularly, Alexia seems to lean into destruction when she comes into contact with people who want to form some kind of emotional relationship with her. At first glance, a generous reading of Alexia is that she attacks those who prey on her or those who overstep boundaries set between a performer and an audience member. The first man she attacks, after all, stalked her, chased her through an empty parking lot, and kissed her forcefully through her unrolled window. A metal hairpin to the ear might be harsh, but he struck first. This kinder interpretation of Alexia is quickly dashed upon her second intimate encounter: a fling with her co-worker Justine (Garance Marillier) that once again ends with the swing of a hairpin. Anyone who witnesses her in a state of vulnerability doesn’t survive long enough for her to develop an emotional link. She is robotic, both in day-to-day life and while killing, effectively rendering her an automaton for the first act of the film.

Alexia’s murders are not premeditated. They are spontaneous, thoughtless acts and as such, they are sloppy. Unlike other films that follow the crimes of serial killers like American Psycho or The House That Jack Built, Titane’s protagonist is caught pretty quickly. By the half-hour mark, Alexia is wanted for murder, and she decides that she might as well take a stab at the much tidier crime of impersonation. In one of the most brutal instances of onscreen self-mutilation, Alexia shears off her hair, tapes down her chest and rapidly expanding stomach, then repeatedly mashes her face against the sink until her nose is bent and bloodied. The wince-inducing sequence leaves her unrecognizable, and she is able to turn herself into the police under the name Adrien Lagrande, a seven-year-old who went missing ten years ago. The boy’s father, a Fire Chief named Vincent (Vincent Lindon), takes one look at the battered Alexia and accepts her as his lost son. No DNA test, no scrutiny, no questions asked. It is with the introduction to Vincent, his open-hearted weeping at his son’s supposed return, that the gore and vulgarity of Titane takes on a new light. Alexia’s death drive begins to wane in the face of Vincent’s candid approach to love and mourning, and the body horror does not exist for mere spectacle, but to prove that even something this dark and twisted and be transformed through contact with love. The bond formed between Vincent and Alexia is, to the audiences’ knowledge, her first and only exposure to feeling like a human and not a machine.

How Does Alexia’s Outlook on Violence Change During ‘Titane’?

Alexia is introduced to us as a monster, a non-human who torments her parents into crashing a car and kills because it’s convenient. She is attracted to cold hard metal over flesh and blood, taking more interest in the piercings on her co-worker’s body than the co-worker herself. She identifies with machines on the emotional level, and on the sexual level, but a car is not something that can reciprocate her affections. Even in this slightly off-world, it is still just a car. It is simply not to connect with her humanity through a machine, no matter how real her feelings are. It’s a one-sided love and can never grow beyond that. After assuming the identity of Adrien, she is cut off from cars. Vincent becomes the only thing around her to connect with, and he is painfully human. Grieving, aging, and desperate to believe this is his son no matter what, he embraces Alexia as if she were his own. When she does finally snap and bust out her trusty weapon, Vincent doesn’t recoil or get angry. He doesn’t even seem particularly surprised by having the sharp end of a pin aimed at him. Instead, he seems to recognize that she is afraid and asks why she wants to leave so badly. “You’re already home.” He says, after which Alexia storms off. It is a change to her status quo: he is neither dead nor running in fear; this has never happened to Alexia before, and the love he is offering is seemingly unconditional.

After this moment, and with increasing severity moving forward, Alexia suddenly has a much harder time practicing violence. She returns with the intent to kill Vincent, but finding him in a vulnerable state after injecting too many steroids, she’s unable to. Alexia sits with him while the resulting heart irregularities peter out, his head in her lap. Where she used to only find love for the mechanical, she now is experiencing empathy for other people. She does not attack or threaten the men who work under Vincent when they are hostile to her, nor does she push off Vincent’s shows of affection.

How Does Alexia Break Out of Her Fixation With Cars?

Alexia’s contact with genuine, paternal love changes how she interacts with the world around her and ultimately breaks her out of her fixation with cars as a replacement for human relationships. Alexia settles more and more into this mundane little life, and she is happier than we ever saw her at the motor show. She joins Vincent in the workplace, eats dinner with him, helps him medicate, and so on. Vincent’s continued acceptance of her as family, despite the initial lurches towards violence, triggers a change inside her and the monster-hood she’d been introduced under begins to dissolve. Her pregnancy underscores this, affirming that she is and always was capable of creating life, not just doomed to follow the instincts of the death drive. Vincent’s need to give love and his intense earnestness are what force Alexia to tap into her own sense of humanity, and while he had always accepted Alexia as his son, she gradually accepts him as a father. The family they form is not based on blood or legal ties, but because they mutually choose to stand by each other. They individually promise to take care of each other, Alexia promising to Vincent’s ex-wife (Myriem Akheddiou), and Vincent directly to Alexia. “I don’t care who you are.” He says upon seeing her pregnant belly. “You’re my son.”

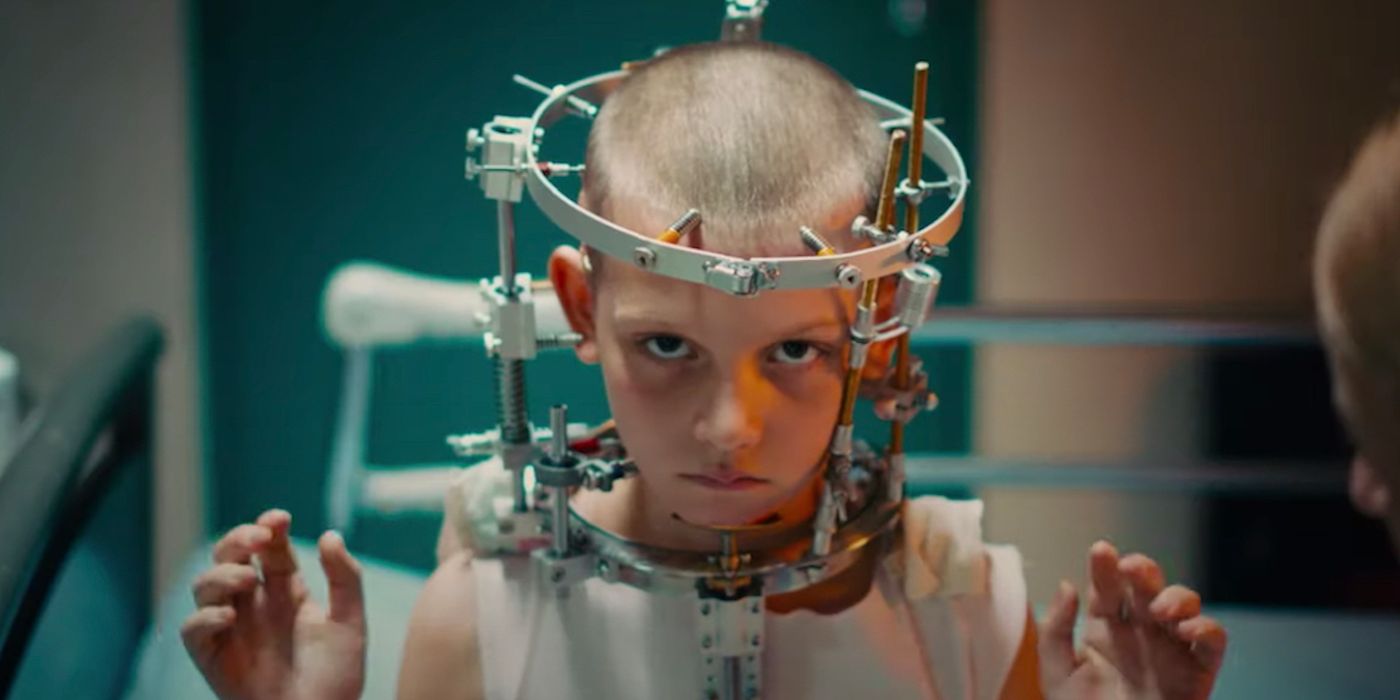

But what about the car baby? Can we go back to the car baby? Yes, Alexia’s pregnancy goes to term. It’s spectacular, it’s gross, and it’s exactly as nasty as the rest of Titane, but once again, it is not without meaning. When Alexia’s stomach begins to split open, leaking motor oil instead of blood, she begs Vincent for help. It turns out that the connection with him really was unconditional, as he has only a moment of hesitation before obliging. He comforts her as metal is revealed under the skin of her stomach, the crash injury from her childhood peeling back in tandem. She confesses her real name, and Vincent helps her through the delivery. It doesn’t matter to him that he’d been lied to, or that she wasn’t his son by blood. At this point, she is his family no matter what, and unlike her relationship with cars, this is a bond that can be reciprocated. Alexia does not survive giving birth. Her child is born with a metal spine and metal plate at the side of their head, but they are undeniably a human child. Despite her initial inability to connect with humans, Alexia’s baby is flesh and blood. Vincent holds the child with the same tenderness that Alexia held him on the bathroom floor, saying: “I’m here,” as the baby wails, promising to look over it in the same way he’d looked over Alexia. Though Alexia doesn’t live through her contact with love, it is still transformative, taking her from an automated force of death to a person capable of compassion. Under all the gore and brutality, Titane is insistent that even the most disconnected people can discover their own humanity.