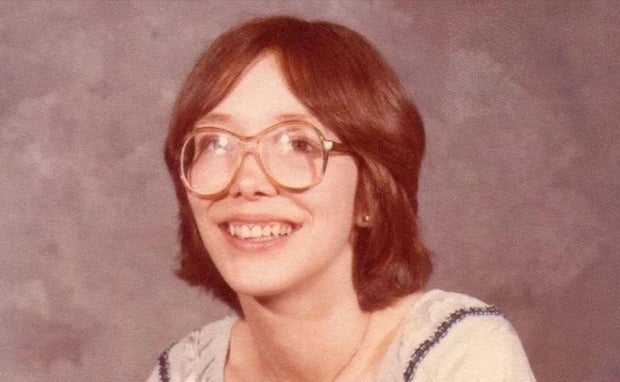

A woman from Missouri who spent more than 43 years in prison for murder his lawyers argue it was committed by a now-discredited police officer who could soon be freed after a judge overturned the conviction. If freed, Sandra Hemme's prison term will mark the longest known wrongful conviction of a woman in US history, her lawyers said.

Judge Ryan Horsman ruled Friday night that Hemme has established evidence of actual innocence and must be released within 30 days unless prosecutors retry her. He said his trial attorney was ineffective and prosecutors failed to disclose evidence that would have helped him.

Hemme's attorneys with the New York-based Innocence Project filed a motion asking for his immediate release.

“We are grateful to the Court for recognizing the grave injustice that Ms. Hemme has suffered for more than four decades,” her lawyers said in a statement, vowing to continue their efforts to have the charges dismissed and reunite Hemme with her family.

A spokesman for Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey did not immediately respond to a text message or email from The Associated Press seeking comment Saturday.

Project Innocence

Hemme was shackled with a leather bracelet and so heavily sedated that she “couldn't keep her head straight” or “articulate anything beyond monosyllabic responses” when she was first questioned about the library worker's death 31-year-old Patricia Jeschke, according to her lawyers.

They alleged in a petition seeking his exoneration that authorities ignored Hemme's “severely contradictory” statements and suppressed evidence implicating Michael Holman, a police officer at the time, who tried to use Hemme's credit card. the murdered woman

“No witnesses linked Ms. Hemme to the murder, the victim or the crime scene. She had no motive to harm Ms. Jeschke, and there was no evidence that the two had ever met,” they said. say Hemme's lawyers.

The judge wrote that “no evidence outside of Ms. Hemme's unreliable statements connects her to the crime.”

“Instead,” he added, “this Court finds that the evidence directly links Holman to this crime scene and the murder.”

It began on November 13, 1980, when Jeschke missed work. Her worried mother climbed through a window of her apartment and discovered her daughter's naked body on the floor, covered in blood. Her hands were tied behind her back with a telephone cord and a pair of stockings were wrapped around her throat. There was a knife under his head.

The brutal murder grabbed the headlines, with detectives working 12-hour days to solve it. But Hemme wasn't on their radar until she showed up nearly two weeks later at the home of a nurse who once treated her, carrying a knife and refusing to leave.

Police found her in a closet and took her back to St. Joseph's Hospital, the latest in a series of hospitalizations that began when she began hearing voices at age 12.

She had been released from that same hospital the day before Jeschke's body was found, and showed up at her parents' house that night after hitchhiking more than 100 miles across the state.

The timing seemed suspicious to law enforcement. When the interrogations began, Hemme was being treated with antipsychotic drugs that had caused involuntary muscle spasms. He complained that his eyes were rolling back in his head, the petition said.

Detectives noted that Hemme appeared “mentally confused” and could not fully understand their questions.

“Each time the police extracted a statement from Ms. Hemme, it changed dramatically from the last, often incorporating explanations of facts that the police had only recently discovered,” her lawyers wrote.

Finally, he claimed to have seen a man named Joseph Wabski kill Jeschke.

Wabski, whom she met when they stayed in the state hospital's detox unit at the same time, was charged with capital murder. But prosecutors quickly dropped the case after learning he was in an alcohol treatment center in Topeka, Kansas, at the time.

Knowing he couldn't be the killer, Hemme cried and said he was the lone killer.

But the police were also starting to look at another suspect, one of their own. About a month after the murder, Holman was arrested for falsely reporting his pickup truck stolen and collecting insurance. It was the same truck spotted near the crime scene, and the officer's alibi that he spent the night with a woman at a nearby motel could not be confirmed.

He had also tried to use Jeschke's credit card at a camera store in Kansas City, Missouri, on the same day her body was found. Holman, who was eventually fired and died in 2015, said he found the card in a bag that had been dumped in a ditch.

During a search of Holman's home, police found a pair of gold horseshoe earrings in a closet, along with jewelry stolen from another woman during a burglary earlier that year.

Jeschke's father said he recognized the earrings as a pair he bought for his daughter. But then the four-day investigation into Holman ended abruptly, many of the details uncovered never being given to Hemme's lawyers.

Hemme, meanwhile, was getting desperate. He wrote to his parents on Christmas Day 1980, saying: “Even though I'm innocent, they want to put someone away, so they can say the case is solved.” He said he could also change his plea to guilty.

“Let it be over,” he said. “I'm tired.”

And that's what he did the following spring, when he agreed to plead guilty to capital murder in exchange for the death penalty being taken off the table.

Even that was a challenge; the judge initially rejected his guilty plea because he couldn't share enough details about what happened, saying, “I didn't really know he'd done it until like three days later, you know, when it was in the paper and in the daily news.”

Her lawyer told her that her only chance of not being sentenced to death was to get the judge to accept her guilty plea. After a break and some training, he gave more information.

This ground was later rejected on appeal. But she was convicted again in 1985 after a one-day trial in which jurors were not told what her current lawyers describe as “grotesquely coercive” questioning.

Larry Harman, who helped Hemme get his initial guilty plea thrown out and later became a judge, said in the petition that he believed he was innocent.

“The system,” she said, “failed her at every opportunity.”